One day in October 2011, Jeffrey Epstein walked into the cavernous lobby of 270 Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. The skyscraper was home to JPMorgan Chase, arguably the world’s most prestigious bank. The sex offender — who barely a year earlier was under house arrest after serving 13 months in a Florida jail — was ushered onto an elevator and whisked to a top floor where Jamie Dimon, the bank’s chief executive, and the rest of the senior leadership had their offices.

Epstein’s crimes have been exhaustively documented, and elements of JPMorgan’s relationship with Epstein have become public via legal proceedings in the United States and Britain. But the full story of how America’s leading lender enabled the century’s most notorious sexual predator has not been told. This account has been pieced together from thousands of pages of internal bank records, sealed deposition transcripts and other court documents and financial data, as well as interviews with people with direct knowledge of the Epstein relationship. Among the findings: Bank officials for more than a decade were anxious about Epstein’s prolific wire transfers and cash withdrawals — JPMorgan ultimately processed more than $1 billion in such transactions for him — and warned senior management about his suspicious activities. But on at least four occasions over five years, the bank’s leaders overrode those objections and continued to serve Epstein.

A 2003 internal report pegged his net worth at about $300 million. The report, which hasn’t previously been disclosed, noted that Epstein’s occupation was advising wealthy individuals like Leslie H. Wexner, the billionaire operator of brands like Victoria’s Secret and the Limited, though bank documents at the time did not list any other clients. That year, JPMorgan attributed more than $8 million in fees to Epstein, making him the biggest revenue generator among investor clients in the private-banking division.

But the report overlooked something that, had it been taken seriously, might have dimmed the bank’s enthusiasm. In 2003, Epstein withdrew more than $175,000 in cash from his JPMorgan accounts — a huge haul, even for someone with millions at the bank. Outside investigators later found that Epstein paid almost that exact amount to women that year. JPMorgan recognized that those withdrawals needed to be reported to federal regulators that monitor large cash transactions. But the bank failed to treat those withdrawals as an early-warning system for itself. Indeed, JPMorgan’s anti-money-laundering specialists subsequently acknowledged that such withdrawals should have alerted the bank to the possibility that Epstein was committing crimes.

JPMorgan, however, was all in. Soon it opened accounts not just for Epstein but also for his companies, including one that handled the affairs of his private island, Little Saint James, off the coast of St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The bank also provided financial backing for Epstein to help Jean-Luc Brunel, a French modeling scout who had been the subject of media reports about drugging and raping women, start a modeling agency called MC2. JPMorgan would ultimately open at least 134 accounts for Epstein, his companies and his associates.

Wittingly or not, the bank was supporting important cogs in Epstein’s sex-trafficking machinery. On the island, Epstein would compel teenage girls and young women to give him nude massages and have sex with him. Some of Epstein’s underage victims said MC2 lured them to the United States with the prospect of paid modeling work. (In 2022, Brunel died by suicide in a French jail cell after being charged with raping teenage girls.)

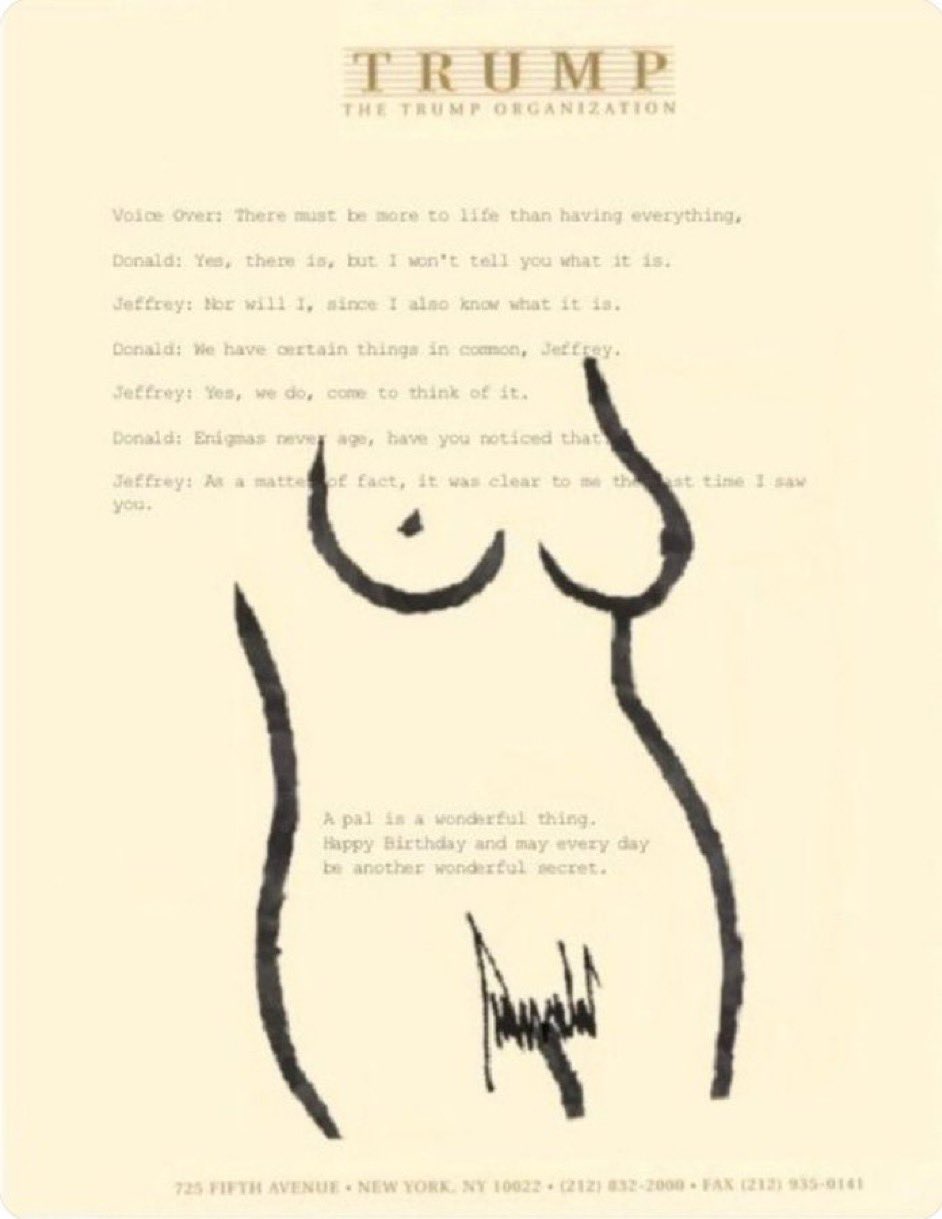

The millions of dollars in fees that Epstein was paying the bank was only part of his allure. Arguably more important, he was identifying potential new clients and business opportunities. In 2003, for example, he introduced Staley to Brin, the co-founder of Google and one of the world’s richest men. Brin hired JPMorgan to help manage his immense fortune — he would eventually park more than $4 billion in assets at the bank — a decision that Staley credited to Epstein. Staley later said in a deposition that a parade of other Epstein referrals — including to Gates, Elon Musk and Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, an Emirati billionaire — followed, though not all became clients.

Just as JPMorgan landed Brin, Epstein made an even more consequential contribution to the bank’s growth. Hedge funds were all the rage among America’s rich, and Staley thought that if he could offer clients access to these investment vehicles, it would help distinguish JPMorgan from rivals. As it happened, Epstein had a useful point of contact: Glenn Dubin, who co-founded a $7 billion hedge fund called Highbridge Capital Management, and his wife, Eva Andersson-Dubin, a former Miss Sweden whom Epstein once dated. Epstein was the godfather to the Dubins’ daughter, and photographs and paintings of the girl were ubiquitous in Epstein’s colossal Upper East Side townhouse. (Epstein would later name Andersson-Dubin as a beneficiary of his estate. Her lawyer said she learned she was a beneficiary only after his death and rejected the bequest.)

In 2004, with Epstein acting as middleman, JPMorgan agreed to pay $1.3 billion for a controlling stake in Highbridge. The acquisition would turn into a landmark for the bank — and for Staley, who described it as “probably the most important transaction in my professional career.” Staley, who by then was running JPMorgan’s asset and wealth management business, was soon reporting to Dimon, the bank’s No. 2 executive and C.E.O.-in-waiting.

Epstein, for his part in arranging the Highbridge deal, pocketed a $15 million fee from the hedge fund that JPMorgan now controlled. The payout reflected a crucial reality: Epstein was the rarest of customers, one whose moneymaking potential extended far beyond his own accounts. It was imperative to keep this superclient happy.