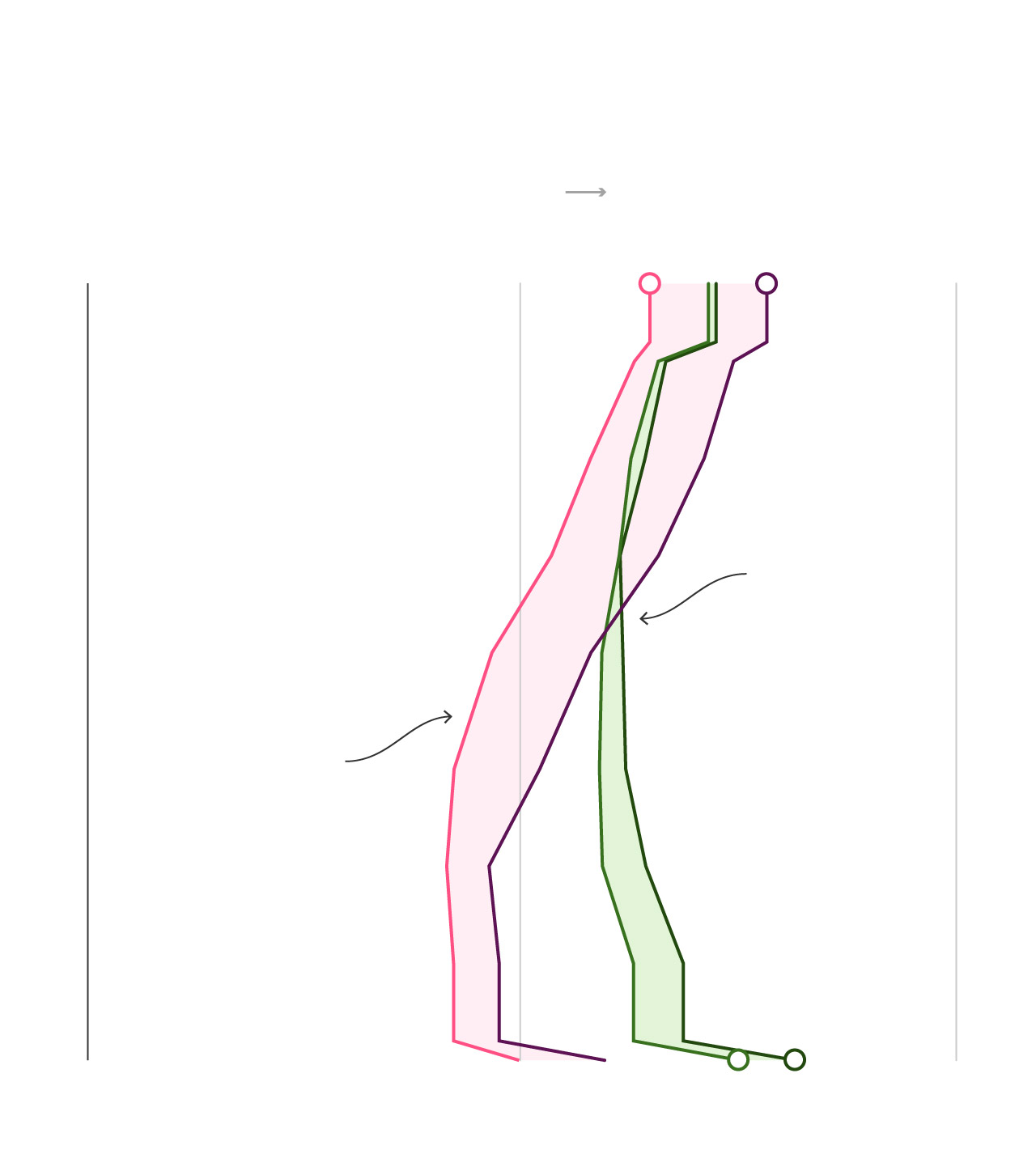

The geographical footprint of early death is vast: In a quarter of the nation’s counties, mostly in the South and Midwest, working-age people are dying at a higher rate than 40 years ago, The Post found. The trail of death is so prevalent that a person could go from Virginia to Louisiana, and then up to Kansas, by traveling entirely within counties where death rates are higher than they were when Jimmy Carter was president.

The mortality crisis did not flare overnight. It has developed over decades, with early deaths an extreme manifestation of an underlying deterioration of health and a failure of the health system to respond. Covid highlighted this for all the world to see: It killed far more people per capita in the United States than in any other wealthy nation.

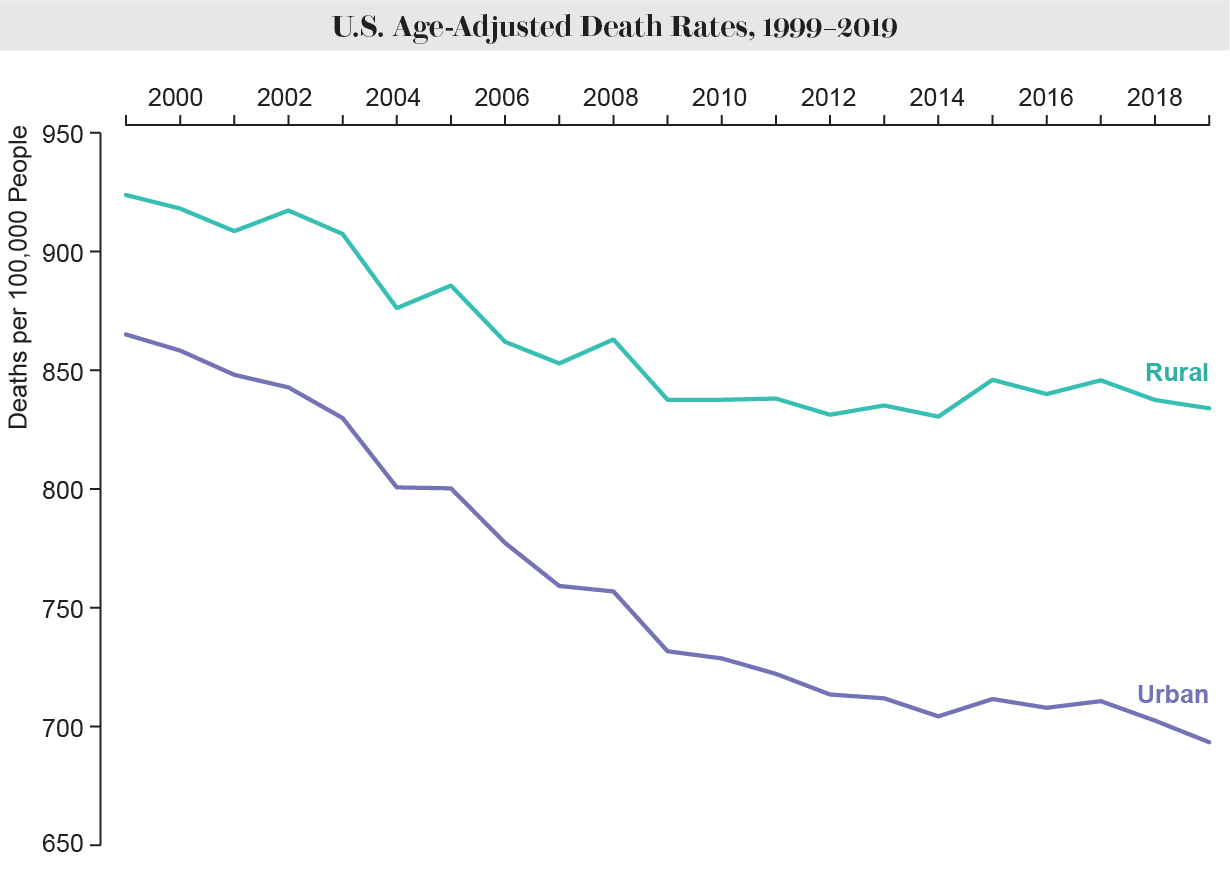

Forty years ago, small towns and rural regions were healthier for adults in the prime of life. The reverse is now true. Urban death rates have declined sharply, while rates outside the country’s largest metro areas flattened and then rose. Just before the pandemic, adults 35 to 64 in the most rural areas were 45 percent more likely to die each year than people in the largest urban centers.

Death rates decreased in 2022 because of the pandemic’s easing, and when life expectancy data for 2022 is finalized this fall, it is expected to show a partial rebound, according to the CDC. But the country is still trying to dig out of a huge mortality hole.

For more than a decade, academic researchers have disgorged stacks of reports on eroding life expectancy. A seminal 2013 report from the National Research Council, “Shorter Lives, Poorer Health,” lamented America’s decline among peer nations. “It’s that feeling of the bus heading for the cliff and nobody seems to care,” said Steven H. Woolf, a Virginia Commonwealth University professor and co-editor of the 2013 report.

In 2015, Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton garnered national headlines with a study on rising death rates among White Americans in midlife, which they linked to the marginalization of people without a college degree and to “deaths of despair.”

The grim statistics are there for all to see — and yet the political establishment has largely skirted the issue.

“We describe it. We lament it. We’ve sort of accepted it,” said Derek M. Griffith, director of Georgetown University’s Center for Men’s Health Equity. “Nobody is outraged about us having shorter life expectancy.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/heal...cy-dropping/?itid=hp-top-table-main_p001_f001