THERE ARE MANY troubling aspects to President Donald Trump's decision to pardon Joe Arpaio: the erosion of the rule of law, the implicit endorsement of Arpaio's racial profiling, the specter of more pardons for loyalists down the line. But equally troubling is the way it underscores the administration's approval of police brutality as a central component of its conception of law and order.

Trump said as much last month, when he spoke to law enforcement officials in Long Island. "Please don't be too nice," Trump said, discussing the handling of suspects. "Like when you guys put somebody in the car and you're protecting their head, you know, the way you put their hand over?" he said by way of example. "You can take the hand away, OK?"

The officers laughed and applauded, but police departments across the country were less cheered. In the week that followed, denunciations poured in as departments distanced themselves from the president's comments.

It would be one thing if Trump's embrace of police brutality were limited to rhetoric, but, as the Arpaio pardon shows, it infects his presidential actions and policy choices as well.

Trump's two favorite sheriffs, Arpaio and Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke, have abysmal records when it comes to treatment of prisoners. Arpaio built a sweltering tent city for inmates in Maricopa County, cheerfully likening it to a "concentration camp." Throughout his 14 years as sheriff, he served detainees spoiled and contaminated food, withheld medical care and ritually humiliated them. He styled himself as "America's Toughest Sheriff," but in reality, Arpaio was one of the nation's most notoriously cruel lawmen.

Clarke, who spoke at the Republican national convention in support of Trump (and whose book Trump endorsed earlier this week), has a similarly egregious record. An inmate in one of his prisons died after being denied water for seven days. Charges of detainee abuse have plagued Clarke throughout his tenure, including over the practice of shackling women who were giving birth. As sheriff he eliminated programs for inmates, restricted food as a form of punishment and woke detainees with bullhorns. Cruelty and deprivation were at the heart of his vision for the county's jails.

Making law enforcement more brutal sits front and center, too, in the Justice Department's policies. The relaunch of the war on drugs, including a return to mandatory minimums for nonviolent drug crimes, reverses recent efforts to reform the criminal justice system and reverse mass incarceration trends.

Likewise, Monday's announcement that the Justice Department would reinstitute transfer of military materiel to police departments indicates that the administration is committed to remilitarization of the police, one of the causes of increased confrontation and lethality in police departments across the nation.

The administration's enthusiastic embrace of police brutality and draconian enforcement is reactionary, part of a backlash to the activism of Black Lives Matter and the broader anti-racist movement. The animating concern of Black Lives Matter is the prevalence of police brutality. In the face of overwhelming evidence of this brutality – caught time and again on camera – Trump chooses not to deny it but to celebrate it.

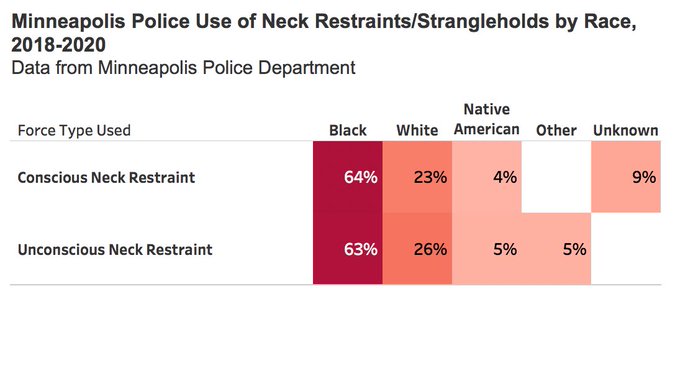

Black Lives Matter is one part of a push for criminal justice reform that centers on the unequal racial impact of policing in America, from stop-and-frisk to racial profiling to inequalities in arrests and sentencing. Trump has never shown any concern for these issues, instead pushing in the opposite direction.

And this is why Trump's comments on race, as well as those made by Arpaio, Clarke and Attorney General Jeff Sessions, matter. Taking up the mantle of police brutality isn't just about cruelty. It's about cruelty to nonwhite Americans – a core plank of the Trump doctrine.

Over the past few years, Trump has styled himself as the law-and-order president. But he's not. He's the brutality president. And if he succeeds in enacting his law enforcement priorities, his legacy will be a more cruel, less just American. Sadly, it's a legacy with which he'll likely be quite happy.

Nicole Hemmer, Contributing Editor for Opinion